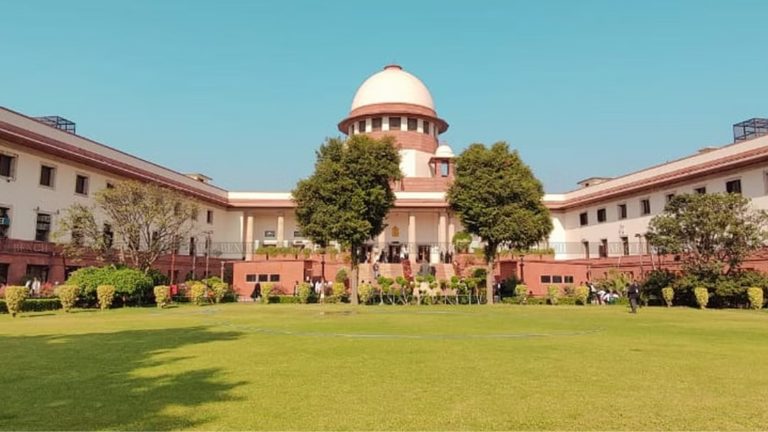

Oct.23,2025 : In a significant pronouncement, the Supreme Court of India (SC) in the case of U.P. Co‑operative Bank Ltd. v. Achchey Lal &Anr.(Civil Appeal No.2974/2016 decided on 11.9.25)has clarified the legal test for determining an employer–employee relationship under laws such as the Industrial Disputes Act, 1947 (I.D. Act) and Factories Act.

The appeal arose from a dispute involving workers engaged in the canteen of the U.P. Co-operative Bank Ltd., where Achchey Lal served as “in-charge”. The High Court of Judicature at Allahabad had earlier held in favour of the workmen being covered under I.D. Act protections. The Bank challenged that decision before Supreme Court.

The SC allowed the appeals of the Bank, emphasising the correct approach to determine when an “employer–employee” relationship arises under the I.D. Act.

The Court reiterated that the label “in‐charge” or “works in canteen” does not automatically render the person a “workman” for I.D. Act purposes. The test must be fact-based and multi-factorial: the contract terms, nature of supervision and control, integration of the workman in the enterprise, whether remuneration is a wage or service fee, and whether the individual carries substantial independence. The Court found that, on the facts, the arrangement did not satisfy the criteria of employment under I.D. Act by reason of lack of direct contract of service, operational control by the Bank and the role being more of a contractor’s worker than bank’s employee. (Detailed factual matrix in the judgment.

This judgment carries wider significance for determining employment relations.

Also read – Deblina Roy has joined GEP Worldwide as Director – Human Resources.

It consolidates that industrial law protections under the I.D. Act will be limited to genuine employer–employee relationships, and not extend by default to persons engaged by contractors or third-party service providers. For organisations (including co-operative banks), this provides clearer guidance on structuring engagement of ancillary workers so as to manage labour-law obligations. For workers and unions, the decision underscores the necessity of establishing the full matrix of control, supervision, remuneration and integration rather than relying on job title or assumption of employment status.

The SC’s ruling in the case reaffirms that determining an employer–employee relationship under the I.D. Act requires a holistic assessment of facts, not merely job designation or organisational attachment. The appeal’s allowance marks a reminder for both employers and workers to carefully evaluate the nature of engagements and roles in light of industrial-law coverage.

Here are the seven key criteria that the Supreme Court of India laid down / reaffirmed in the case for determining whether an employer–employee relationship (particularly under the Industrial Disputes Act, 1947) exists.

The Seven Criteria

- Control over the work and the manner of its execution

The Court emphasised that the earlier “control test” (i.e., whether the hirer has a right to direct what work is done and how it is done) remains relevant. In the case the bench noted that “the right to supervise and control the work done … not only in the matter of directing what work the servant is to do but also the manner in which he shall do his work” is a foundational test. It is not merely formal control but the substantial ability to direct and supervise. The Court stated: “the degree and level of control required would depend on the facts and circumstances of each case.”

- Integration test / level of integration into the employer’s business

A person is more likely an employee if he or she is integrated into the business of the hirer (i.e., part of the employer’s organisation) rather than being a mere accessory or external contractor. In the case the Court reaffirmed that this factor must be looked at: Are the workers functioning as part of the principal employer’s enterprise (and thereby subject to its rules, oversight, business exigencies), or are they external to it?

- Mode/manner of remuneration

One factor is how the worker is paid: Is it salary or wages, deductions like PF, supervision, leave, etc (indicating employment)? Or payment for a result/service (contractor) or piece-work?The Court in the case said that the manner in which remuneration is disbursed is relevant, specifically whether the principal employer pays the worker as a wage for services or through a contractor/third-party.

- Economic control / who bears profit or loss / who supplies tools etc

The “economic reality” or “who owns the assets, bears the business risk, supplies materials or tools” test features in recent jurisprudence. In the case Court mentioned that whether the worker is performing labour for himself/on his own account or for the employer is relevant (thus economic control is a factor).

- Whether the work is being done for oneself or for a third-party/employer

Closely tied to economic control, but emphasises whether the person is carrying on his own business (on his own account) or is absorbed in and working for the employer.The Supreme Court reiterated that the test includes “whether a person who has engaged himself to perform services is performing them as a person in business on his own account.”

- Who provides tools/ materials/ premises; who determines where work is done

Although sometimes subsumed under control or economic control, jurisprudence emphasises whether the hirer supplies the tools/apparatus, the premises, and thereby indicates employment rather than an independent contractor. SC lists this factor as part of the multifactor test: ownership of assets and provision of materials are relevant.

- Context/totality of the circumstances (no single factor decisive)

Importantly, the Court stressed that no single criterion is determinative. What matters is the “totality of the facts and circumstances” of each case, balancing the factors that point in favour of an employment relationship and those pointing against. In this case,the Court emphasised that each case must be viewed in its factual matrix: “the degree and level of control required would depend on the facts and circumstances of each case.”

While often referred to as a “six-test” or “seven-factor” approach, the Court effectively bundles many of the factors under a broad “multifactor test” framework.The judgment builds on prior authority (including Sushilaben, Balwant Rai Saluja & others cases ) but clarifies that in the Industrial Disputes Act context, one must look beyond mere titles or job descriptions.

It also reiterates that the burden of establishing that someone is a “workman” or employee under the I.D. Act lies on the person claiming that status.